It was a little more than three years ago that the message came from my pal Nancy that our mutual high school friend, Sue, had taken her life.

I was shocked and saddened to think that my friend apparently had come to feel so hopeless. Sue and I had been good buddies in school, but as can happen with old chums, she and I had lost touch over the years. I hadn’t seen her in more than a decade and was only aware of the basic facts of her life at that point: town of residence, marital status, career — that sort of information. When I heard the news of her death, I wished that she and I had reconnected at some point.

Our connections to others are important for our mental health, according to Josh Allen, RN, C-AL, a founder, past president and current board member of the American Assisted Living Nurses Association. He knows about suicide, too. Over the years, a few residents in communities in which he has worked have attempted to take their own lives, he said, and a couple of them have been successful.

“There’s a real risk of suicide in our settings, and we have a responsibility as professionals to watch for the warning signs and intervene accordingly,” Allen told those participating in a recent AALNA / National Center for Assisted Living webinar on the topic.

Any discussion of suicide must include a discussion of depression, said Allen, director of InTouch at Home, a home care program operated by California-based senior living provider Senior Resource Group, which has 18 communities across five states. “Although most people who are depressed are not, in fact, suicidal, we do know that two-thirds of those who commit suicide suffer from a depressive illness,” he said.

Research conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has found that depression is the seventh most common chronic condition among assisted living residents, affecting as many as 28% of them, Allen said.

Women are twice as likely as men to experience depression, he added, and only one in three people (male or female) who is depressed actually receives treatment for the condition. “This is a true medical problem. It requires the appropriate treatment, whether that’s in the form of therapy, inpatient care or medications,” Allen said. “It’s not just a problem that people have to get over and start to feel better.”

Depression is not a normal part of aging, Allen added, although some factors that can contribute to depression — chronic health conditions, the need for assistance with activities of daily living, lack of social support and the death of loved ones — can be associated with aging. Residents can be particularly vulnerable to depression when they first move into an assisted living community, he said, because the move can signify the changes they are experiencing.

Signs of depression can include a lack of energy, a loss of interest in previously enjoyed activities, intentional withdrawal or isolation from others, a change in appetite or sleep, feelings of worthlessness or guilt, difficulty concentrating and making decisions, and poor self-care. “The key point here is some sort of change to what is normal for that person, some sort of change to their baseline,” Allen said.

The Geriatric Depression Scale, a well-validated screening tool involving 15 questions you can ask a resident, can help you determine whether a resident might have depression, he said. Be sure to share the results with the resident’s physician. “It’s not our job to diagnose our residents, but we do play a key role in helping their clinician,” Allen said.

So how can those who work in assisted living communities help address depression and prevent suicide among residents? Allen provided the following advice:

- Make the community as accessible as possible. Make it easy for visitors to socialize with residents by offering plenty of parking and physically accessible spaces within the community.

- Make it easy for residents to visit family and friends by offering transportation services and supplemental transportation options for social appointments in addition to medical appointments.

- Ask residents about their backgrounds and interests, and introduce them to other residents — and perhaps even staff members — who enjoy similar activities. Create a database to keep track of the information.

- Ask a resident to help a new community member get acclimated, or form a welcoming committee of staff members and residents for that purpose.

- Create opportunities for one-on-one engagement for residents who don’t enjoy group activities. Involve staff members, volunteers or other residents.

Know what is typical behavior for each resident. If possible, talk with family members or friends who have known a resident for a long time.

Know what is typical behavior for each resident. If possible, talk with family members or friends who have known a resident for a long time.- Provide access and support for those looking for help. Consider hosting an event for residents to talk about depression and how to access support networks.

- Carry out the treatment plan devised by the resident’s physician if depression has been diagnosed in a resident, and provide feedback to the physician about the plan’s effectiveness.

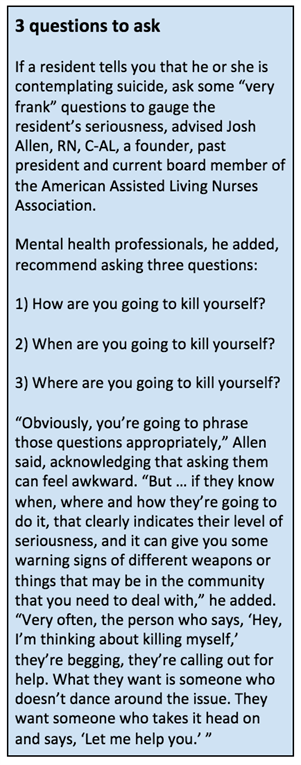

- Learn the warning signs of suicide, and watch for them. Be alert to residents who are giving away their possessions or contacting friends and relatives with whom they haven’t spoken in years or decades (as a way to say goodbye). “If you suspect a resident may be suicidal, respect your gut feelings,” Allen said. “Don’t try to talk yourself out of it.”

- If you notice warning signs in a resident, do not leave him or her alone. Call 911 if you believe the threat is imminent, and notify the resident’s physician.

- If a resident ends his or her life, help other residents address their feelings about it. Consider inviting health professionals to conduct support group sessions during which suicide and depression are discussed.

- Think about the potential for risk in your community — some of the ways residents could attempt to end their lives, “as unpleasant as it might sound,” Allen said — and try to reduce the risk. In recent years, assisted living community residents have attempted suicide by jumping from a high floor, cutting their wrists with broken glass or a knife, hanging, electrocution, overdosing on medication and shooting with a firearm, Allen said. The latter two methods are common choices of women and men, respectively, he said.

Lois A. Bowers is senior editor of McKnight’s Senior Living. Follow her on Twitter at @Lois_Bowers.