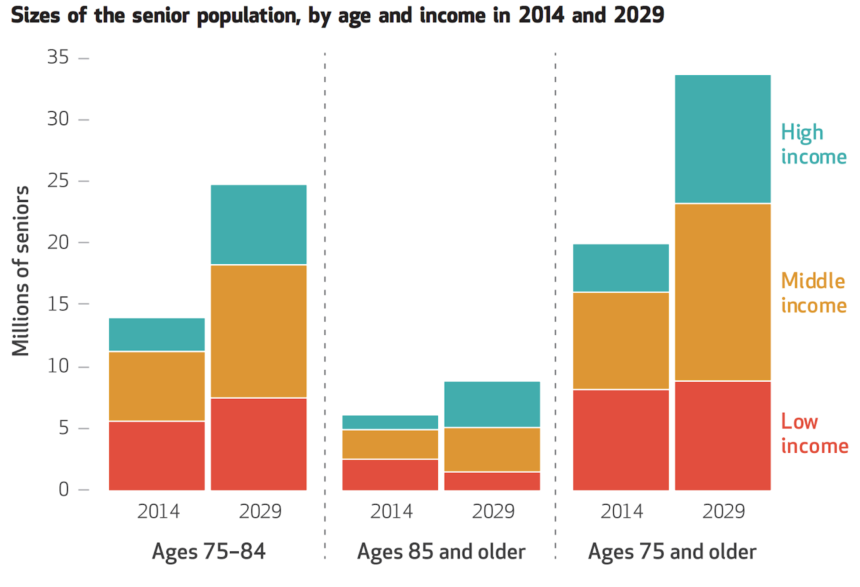

Fifty-four percent of the 14.4 million middle-income older adults in 2029 in the United States will lack the financial resources to pay for senior housing and care, and a combination of public and private efforts will be needed to address the looming crisis, projects a study funded by the National Investment Center for Seniors Housing & Care and published online today by Health Affairs.

The figure considers those who would be able to sell their homes and use all of their annual financial resources to pay for senior housing and care. The percentage increases to 81% if it includes middle-income older adults who would be able to keep their homes but commit the rest of their annual financial resources to cover costs associated with senior housing and care.

“This is a wake-up call to policymakers, real estate operators and investors,” said Bob Kramer, NIC founder and strategic adviser.

The study, by researchers from NORC at the University of Chicago, the University of Maryland School of Medicine, Harvard Medical School and NIC, is believed to be the first to project both the housing and healthcare needs of older adults based on income. The AARP, the AARP Foundation, the John A. Hartford Foundation and the SCAN Foundation also provided support.

Kramer and David Grabowski, Ph.D., an author of the study and professor of healthcare policy in the Department of Health Care Policy at Harvard Medical School, told McKnight’s Senior Living they were struck by the absolute size of the potentially affected group.

“We see this huge number, 14.4 million middle-income seniors by 2029,” Grabowski said. “We knew the number would be big, but I thought it was pretty staggering.”

The study looked at adults aged 75 or more years. Grabowski and fellow authors, using data from the 2014 Health and Retirement Study, defined the “middle-income” cohort as those who, in 2029, would have incomes of $25,001 to $74,298 (in 2014 dollars) if aged 75 to 84 or incomes of $24,450 to $95,051 if aged 85 or more years.

“This income group is generally too wealthy to qualify for public means-tested programs, yet not wealthy enough to pay the costs at many seniors housing communities for a sustained period of time,” the authors wrote. The problem, they said, will be compounded in the future by lower savings rates and the lack of pensions among baby boomers as well as the decreasing number of family caregivers per older adult.

The researchers projected that more than half of all middle-income older adults will not have enough assets to cover the projected average annual cost of $62,000 for assisted living rent and other out-of-pocket medical costs a decade from now, even if they sold their homes and also committed all of their annual financial resources to pay for it. If they didn’t sell their homes to use the equity for senior housing, then only 19% of middle-market older adults would have the financial resources to afford housing and care in 2029, they said.

Both Grabowski and Kramer commented that middle-income older adults in 2029, as a group, will be more diverse and more educated than today’s middle-income seniors — but also sicker. A projected 60% of the group will have mobility limitations, and 20% will have high healthcare and functional needs, having at least three chronic conditions and needing help with at least one activity of daily living. Eight percent will have cognitive impairment.

“That’s something that I think is a really important takeaway from this work, that their health and mobility needs are likely going to demand additional care,” Grabowski said.

Private and public solutions needed

“Any solution is going to be a balance of the private and public responses,” Grabowski said.

Potential private-sector solutions listed in the paper — some in use today, but not widespread, according to the authors — include:

- Charging less rent and accepting lower investment returns and profit margins.

- Operating mixed-income communities, where the higher rents paid by some residents can be used to subsidize the rents of those with lower incomes.

- Offering more basic housing products.

- Taking advantage of technology to reduce operating costs, increase staff efficiency or enable residents to be more self-sufficient.

- More formally involving family caregivers, outside volunteers and healthier residents to offset staffing costs.

- Using à la carte pricing to separate care and services from housing to increase flexibility for some residents.

- Establishing Medicare Advantage plans, individually or jointly with other operators, to offer on-site medical services.

Potential public-sector actions, according to the authors:

- Offering tax incentives for developers and operators who serve middle-income older adults.

- Establishing higher limits for low-income tax credits and other programs to include more middle-income older adults.

- Expanding subsidies or voucher programs for older adults.

- Creating new incentives to encourage long-term care financial planning.

One solution that looks especially promising, Grabowski said, is Medicare innovation.

“We’re seeing movement there from a policy perspective with the recent decision to allow home care to be covered as a supplemental benefit in Medicare Advantage,” he said. “That’s a really exciting development. We’re seeing a lot of these [models for dually eligible beneficiaries] that are covering a broader set of services. So I really believe that’s kind of the future here.”

Another promising solution, Grabowski said, is housing subsidies or credits to encourage entry of private-sector groups. But he said he is “less bullish” on Medicaid as a solution.

“I just don’t know that we can heavily lean on Medicaid, given the number of boomers that we’re going to have,” he said. “That’s not to say Medicaid can’t be part of the solution — I just mentioned some of these blended Medicare / Medicaid models for duals — but I just don’t see Medicaid being our primary way forward supporting this middle-income group.”

Kramer agreed, while noting that states are experimenting with home- and community-based service waivers via Medicaid, “providing services that traditionally would not have been provided.”

“One of the areas for exploration will be, do we continue to force people to spend down into poverty before we give them the support they need?” he said, referring to the process whereby individuals qualify for Medicaid. “The research would indicate that by doing that, they’re liable to be in worse health and more likely to be hospitalized or to be in higher-cost settings than if we had intervened earlier with the sort of coordinated housing setting where you’re basically able to address food issues, transportation issues and lack of social interaction and social connection issues, as well as effectively manage their chronic conditions.”

Senior housing, he said, has “enormous opportunities to be, quite frankly, the preferred consumer setting, the lower-cost setting, and the place that produces the best health outcomes, but that means getting out of silos” and integrating housing, long-term services and supports and healthcare.

Innovations in financing also are needed, Kramer said.

“By this, I mean financing of the building so that, for instance, you don’t have to continually get new loans or new infusions of equity — for instance, construction loans and transition loans to get to HUD or to Fannie and Freddie and so forth,” he said. “Each time, there are lots of fees associated with that, and perhaps that process could be streamlined, for instance, with one loan rather than having to do a series of multiple ones.”

The study is the subject of a press conference this morning. Two additional events were planned — today’s in Washington, D.C., for policymakers, and one in New York City for investors.

“I think the third step there would actually be to start bringing those groups together and talking about potential models that would potentially build on private-sector innovation with some public-side solutions,” Grabowski said.

“We actually did this [study] partly in response to the provider community saying, ‘Look, we believe there’s going to be a market there that needs to be served and that we can serve, but first we have to understand. We need numbers,’ ” Kramer said.

“Right now, the industry has an opportunity to be at the table and forge solutions that can work, rather than being forced to follow solutions that aren’t really solutions but are just knee-jerk reactions to a crisis,” he said.