Emergencies can strike in a multitude of different ways when caring for older adults, and having a clear plan for disaster preparedness is critically important.

I am an emergency medicine physician who specializes in geriatrics, and our resident education team asked me to help design a disaster scenario involving a fire in a long-term care facility.

From our emergency medicine residents (physicians in training), we have them focus on triaging facility residents/patients by acuity and how local disaster response agencies, such emergency medical services and trauma centers, work together. But it made me wonder how directors and leaders of long-term care facilities put together disaster preparedness plans.

Every assisted living community, group home and skilled nursing facility is supposed to have a disaster preparedness plan and an evacuation plan, but we have seen in recent disasters over the past few years (notably Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans and Hurricane Harvey in Texas) where some facilities did not have or did not appropriately execute their evacuation plans. So how do we take something that is a document on paper and make it into a real, usable plan?

The state of Ohio has Rule 3701-16-13, which mandates a certain number of full fire drills with evacuation of the building and a tornado drill annually. Although this rule may help for a sudden, short-term disaster, such as a building fire, it would not be sufficient for a larger longer-term disaster, such as a fire sweeping through the city, or a hurricane.

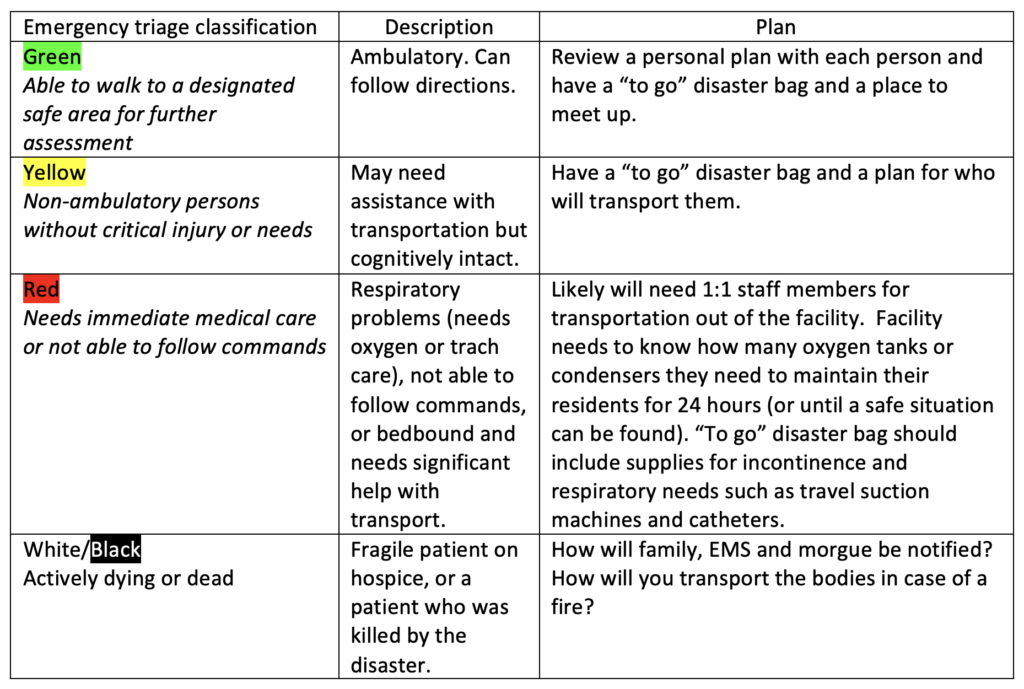

Perhaps senior living and care settings can borrow some of the mass casualty incident triage criteria that emergency departments use (see below), because in the moment of an evacuation or disaster, you need every person — staff member and resident — to operate at the height of their abilities. Especially for those in disaster-prone areas, all residents should have a disaster “to go” bag with copies of medication lists and important papers they can grab for evacuation. If you have time to plan for a big storm coming, then food/snack/water packs are good as well.

Each facility’s plans must consider the residents you care for and their needs for the next day (or more). If your community includes stand-alone or senior living condos, then several additional provisions should be set in place.

If a resident has fallen or is injured, then it is imperative that he or she has a way to contact emergency services, whether that is through a wearable alert system, smart watch or easy-to-reach cell phone. Once EMS responds, it needs to be able to enter the property. Some residents install a lockbox for emergency personnel to access in that instance. Or ensure that multiple people have master keys so that residents can be checked on and evacuated quickly.

Can some of those people be assisted in evacuation by local family members? Also, each independent living resident may need his or her own specific plan.

Another critical element to consider is how to ensure that the caregivers and families of your residents know where they are. Many example plans online say to “notify the families” but don’t consider the how. Do you have a cell phone list of emergency contacts that is easy to access in case computers and the internet are not working? Or a disaster alert text line they can sign up for?

Remember that internet and power may be down. Signs on the community doors with information on where the residents are and how to contact staff members could be helpful if a long evacuation is expected and families may drive by hoping to check on their loved one. Are families given a copy of the community’s disaster preparedness plan when their loved one enters your care so that they know what to expect?

In the emergency department, we say that the best disasters happen at shift change, when you have extra staff members there during sign out. But consider that your staff members may have to rush home and help evacuate their families as well.

There are heroic stories of staff members staying with their residents for untold days to manage care during a disaster. Do you have an emergency staffing plan?

Thanks for reading this, and we hope that it will make some of you consider dusting off those binders of emergency preparedness instructions in your nurse manager’s or other manager’s office and giving them a second look. And thanks for doing all that you do to help our older adults and vulnerable patients live full and happy lives.

Lauren Southerland, MD, MPH, is a clinical associate professor in the Department of Emergency Medicine and director of clinical research for emergency medicine at The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center, Columbus, OH. She specializes in geriatrics and emergency preparedness for older adults. Lucas Krupinski holds a Bachelor of Science degree and is a clinical research assistant.

The opinions expressed in each McKnight’s Senior Living guest column are those of the authors and are not necessarily those of McKnight’s Senior Living.

Have a column idea? See our submission guidelines here.