“The first lesson of economics is scarcity: There is never enough of anything to satisfy all those who want it. The first lesson of politics is to disregard the first lesson of economics.” —Thomas Sowell

“There are no solutions. There are only trade-offs.” —Thomas Sowell

The senior living and care business encompasses a wide range of services, including independent living, assisted living, memory care, skilled nursing and home care (including home care provided in the aforementioned settings). Private-market forces prevail in independent living and, somewhat less so but predominantly, in assisted living. Government funding and regulation prevail in home care, skilled nursing and, less so but significantly, in assisted living. By most measures, the more market-based independent and assisted living sectors fare better economically over time than the more government-dependent sectors. Why?

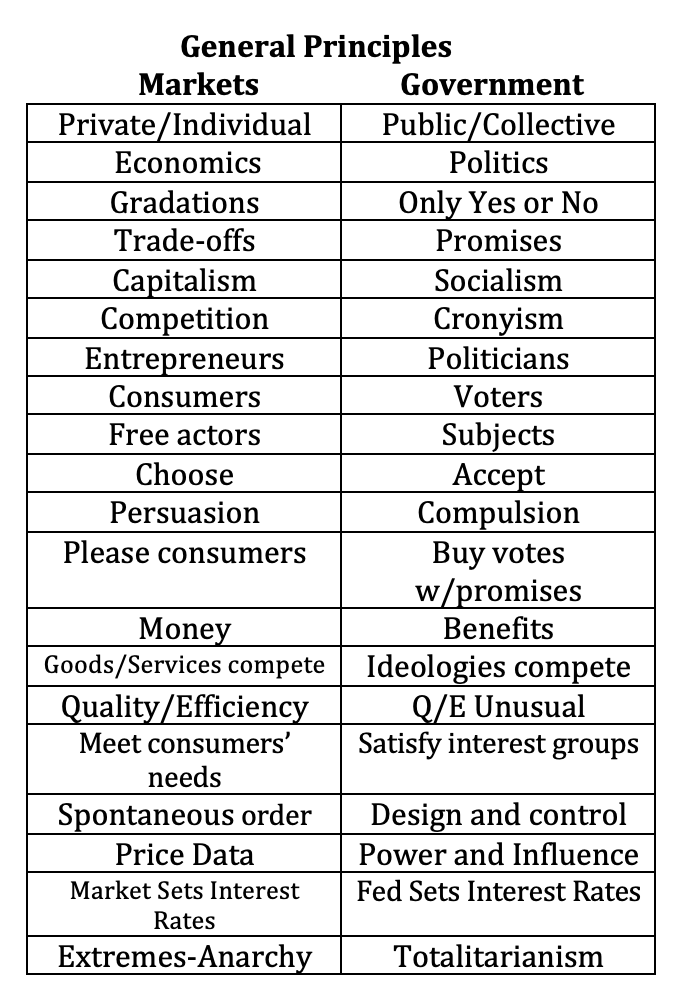

Markets operate on different principles than government. As the prevailing trend in long-term care for decades has been away from private markets toward more government involvement, it behooves operators to compare and contrast the principles and results of both private and public financing systems. Let’s consider general principles first and then home in on their results for senior living and care. Perhaps we can reach conclusions that will guide our public policy preferences.

Economics explains markets. Markets are private, individualistic and maximized by capitalism. Politics explains government. Government is public, collectivist and bends toward socialism.

In the market, free-acting consumers vote with their dollars for (that is, they choose) whatever they want in the quantity and quality they desire. Government subjects can only vote yes or no (that is, they accept) for politicians or ballot measures with no gradations for preference, amount or quality.

In markets, entrepreneurs compete by creating or identifying and meeting consumers’ needs based on quality and efficiency. In government, politicians compete by satisfying interest groups with benefits paid for by others, and with quality and efficiency notoriously absent.

In markets, millions of transactions between willing buyers and sellers create spontaneous economic order, set interest rates (the price of money) through supply and demand, and generate price data that tell investors and businesses how much of which products and services to produce. In government, the Federal Reserve sets interest rates based on balancing political powers and influence resulting in asset bubbles, malinvestment and economic inequality.

Government, markets and long-term care

How has government affected long-term care? By making nursing home care — including room, board, medical care, laundry services, etc. — virtually free for anyone who cannot otherwise afford it, government created the delivery system’s institutional bias and generated a huge, politically powerful nursing home industry.

By paying too little to ensure quality nursing home care, the government alienated consumers, leading those who were financially able to seek alternative care venues. In response, the market created a mostly private-pay alternative, assisted living.

Access to publicly financed nursing home care after the care is needed, facilitated by large Medicaid income and asset exemptions, desensitized the public to long-term care’s risk and cost, impeded development of a private market for the home- and community-based care consumers prefer, and crowded out private sources of financing that the delivery system desperately needs, such as revenue from home equity conversion and private long-term care insurance. Government involvement has left America with a long-term care service delivery and financing system fraught with problems of access, quality, low reimbursement, discrimination and institutional bias. Yet most analysts and politicians want to double down on public financing and regulation with new, compulsory social insurance plans.

How could a more market-oriented approach improve long-term care? People left to their own devices would spend their money on independent living, home care and assisted living — in that order. They would seek nursing home care only when medically necessary.

If the government didn’t finance most expensive long-term care, even for the middle class and affluent, then consumers would worry about that risk and save, invest and/or insure for it. If Medicaid didn’t exempt between $603,000 and $906,000 of home equity from long-term care liability, then people would have a stronger reason to plan, prepare, save or insure for the risk, to protect their wealth.

With home equity, private insurance and genuine asset spend-down unmitigated by Medicaid eligibility loopholes pried wide open by Medicaid planning attorneys, private financing at full market rates would flow into all levels of long-term care. New revenue and capital would invigorate the whole continuum, encouraging more innovation by investors and delivering better services for consumers. Some needy individuals would remain, but their needs could be met by private charity and, if necessary, a vastly reduced public safety net program.

Applying the general principles of markets and government identified above to the practical challenges of long-term care points to only one conclusion: We need to rely more on markets and less on government to improve both.

Stephen A. Moses is president of the Center for Long-Term Care Reform and the author of “Medicaid and Long-Term Care” and “How to Fix Long-Term Care.” Reach him at [email protected].

The opinions expressed in each McKnight’s Senior Living guest column are those of the author and are not necessarily those of McKnight’s Senior Living.